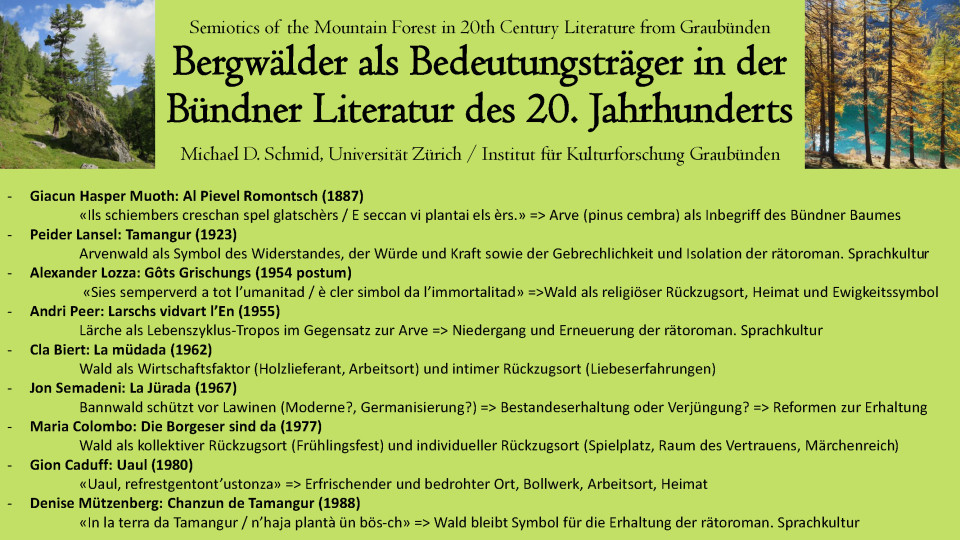

There are different perspectives on the alpine space and landscape of Graubünden in 20th century literature. A particularly interesting type of landscape is the mountain forest, as it is functions not only as a scenery for diegetic actions, but has specific semiotic connotations of cultural kind. Especially in the romansh literature, trees and forests are important symbols for the cultural identity and resistance. Two examples from engadinian writers may illustrate that. They are both dealing with cultural semiotics and even an anthropomorphisation of the trees.

A great example is the famous poem Tamangur (1923), written by Peider Lansel. It describes an old arolla pine forest called “Tamangur” way up in the Val S-charl. The arolla pine often grows in high alpine zones on rocky grounds and has an extraordinary strength against wind and weather. These characteristics make that tree a perfect symbol for the romansh culture, which, according to Lansel’s poem, is also deeply connected with and “rooted” in the high mountain regions, and need to be strong against external influences as well. Wind and weather stand semiotically for the foreign cultural influences that threaten the Romansh. The loneliness of the forest stands for the isolation of the romansh community due to emigration. The age of the wood represents the ancient dignity, that makes it worthy to stand against the threats and defend the local language and culture. Thus, the mountain forest serves as a multi-levelled symbol of the people of romansh Graubünden and their collective cultural identity.

The motif of the mountain forest as a bastion against change has been retaken by many authors from romansh Graubünden. The tale La jürada (1967) from Jon Semadeni for instance, shows a complex reflection of the dichotomy of conservative and progressive approaches onto culture. The plot narrates the life of a young forester in a mountain village. As he has learned at university, the forest has to be rejuvenated, to keep him strong. This means, to cut down some older trees and plant younger ones. Obviously, this reflects the idea, that a culture only can be conserved by reforming it and include newer elements – a middle path between the extremes of cutting down all trees (abolish culture and tradition) and leaving the forest untouched, although it grows old and weak (let culture become outdated). The story reflects on the opportunities to handle with tradition and change, and creates by its own poetical aesthetics an innovative artwork between those poles.

Of course, the semiotics of the mountain forest in literature from Graubünden are not fixed and only related on resistance and tradition. Forests appear in stories and poems as

· a space for individual or collective retreat from the every-day’s life

· a magical world of fantasy legends and fairy tales

· a symbol of nature in opposition to civilisation (especially the expansion of tourism and energy infrastructure)

· a religiously connoted space, that symbolises the creation or even the eternal

· an idyllic place for amorous experiences

· a location of traditional economic activities like wood cutting and hunting

· an entity that is protecting, but needs protection as well (cultural and ecological)

This list shows a bright variety of possible cultural meanings, a mountain forest can stand for or being associated with. But all these cultural meanings of forests have something in common: they construct in different and often complex ways the forest as a constant counterpart to the changes of the modern world. The analysis of this literary reflection of the mountain forest can help to understand the complexity of collective and individual cultural identity building.

Quiz question

Welcher Baum ist ein häufiges Symbol für die rätoromanische Sprachkultur?

Bergulme

Arve

Birke